I watched a customer service model collapse in real time.

The e-commerce platform had trained its model on three years of support history: product questions, shipping issues, account problems. It handled 80% of routine inquiries without escalation. Then they fine-tuned it on refund requests because the holiday season was coming.

Within hours of deployment, the model answered product questions with refund logic. When someone asked about battery life, it offered them store credit.

The model hadn't forgotten gradually. It had catastrophically overwritten everything it knew about product support while learning refunds.

What is catastrophic forgetting?

Catastrophic forgetting is a phenomenon where neural networks lose previously learned knowledge when trained on new tasks. Unlike human learning, where new information typically adds to existing knowledge, neural networks overwrite the weight configurations that encoded prior capabilities.

Why does catastrophic forgetting happen?

Neural networks store everything they learn in weights i.e. the numerical parameters that determine how input transforms into output. There's no separate memory system. No knowledge graph sits alongside the neural network. Just weights.

When you train on new data, the model calculates gradients: "if I adjust this weight in this direction by this amount, I'll reduce my current error." The same weights that encode prior knowledge must also encode new knowledge. The network can't partition itself into "these weights for invoices, these weights for receipts." Every weight contributes to every task.

The forgetting isn't gradual degradation, rather a sudden collapse. Performance on the original task can cliff-dive within hours of training on the new task.

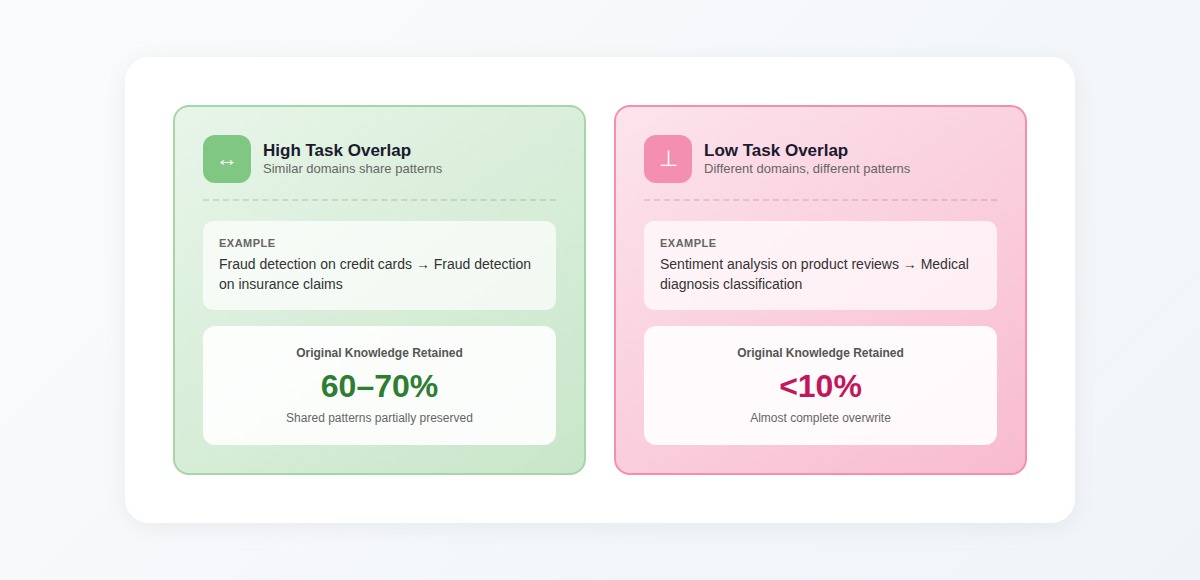

The severity depends on how much the tasks overlap:

This is fundamental to how neural networks learn through gradient descent. When you update weights to learn task B, the optimizer doesn't know task A ever existed. No term in the loss function says "maintain task A accuracy." Every gradient update optimizes for the new task only.

I've traced what happens during forgetting by examining weight distributions before and after fine-tuning. When you train a model on task A, certain weight values become critical—a specific layer might develop weights concentrated around 0.7-0.8 because that range captures task A patterns. Train on task B, and those same weights shift to completely different values. The configurations that made task A work are gone.

The speed correlates directly with training aggressiveness. High learning rate on task B: task A performance collapses within minutes. Lower learning rate: forgetting happens more gradually, but it still happens.

Knowledge in neural networks uses distributed representations. A single weight participates in encoding multiple pieces of knowledge simultaneously. A weight in layer 3 of a vision model might help detect edges in cat images, curves in bird images, and textures in dog images. You can't adjust that weight without affecting its contribution to everything else.

Why catastrophic forgetting matters

Most production AI systems need to improve continuously. Customer support categories change. New fraud patterns emerge. Document formats evolve. The business value of AI depends on models that adapt without requiring complete retraining every time something changes.

Catastrophic forgetting makes this nearly impossible with naive fine-tuning. Each update risks destroying existing capabilities. Teams get trapped: they can't add new capabilities because doing so breaks production functionality, but they can't ignore new requirements because the model becomes less relevant over time.

The operational costs are stark. Teams face two bad options:

- Retrain from scratch: One team needed to add a simple document format capability — 2,000 new examples. Retraining meant reprocessing their entire 40-million-example dataset. At their compute costs, that's $180,000 for what should be a simple update.

- Fine-tune on new data only: A team adding financial document understanding saw accuracy on financial docs improve from 62% to 91%. But legal contract analysis dropped from 94% to 79%. The model didn't gain capability, it traded one for another.

This is why benchmark accuracy is a snapshot, not a capability. A model that scores 95% on a leaderboard today might score 60% after next week's fine-tuning. Teams optimize for leaderboard position, publish the result, then fine-tune for production needs. The published score describes a model that no longer exists.

Catastrophic forgetting enforces batch updates rather than continuous learning. Production AI systems can't learn from usage in real-time. Every customer interaction that reveals a gap gets added to a queue. You collect data, wait until you have enough to justify retraining, then take the system offline, retrain from scratch, and redeploy. A customer problem identified in January isn't fixed until April.

Mitigation strategies and their limits

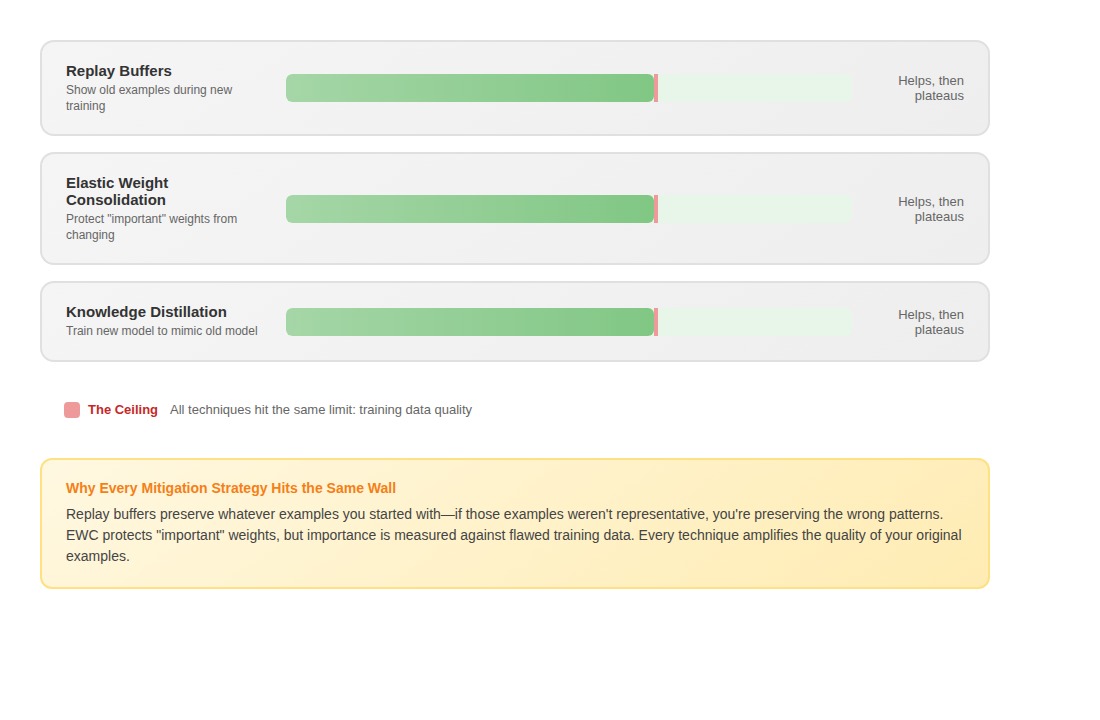

Most approaches fail in predictable ways. The problem isn't that these techniques don't work, it's that they all amplify the quality of whatever training data you started with.

Replay buffers periodically show the model old examples while training on new ones. The problem surfaces about three training cycles in. One team trained a model across different product lines. By the fourth product, performance on Product A had degraded by 40% and not because the replay buffer failed mechanically, but because the original Product A examples weren't representative enough. The buffer faithfully preserved examples that didn't capture the actual distribution.

Elastic weight consolidation (EWC) tries to identify which parameters matter most for previous tasks and prevent them from changing too much. But importance is relative to the training distribution. If your training data was systematically flawed, you're protecting the flaws. One team discovered their contract training data had licensing agreements mislabeled as service agreements. EWC actively prevented the model from correcting this error because it identified the weights encoding the wrong pattern as "important."

Knowledge distillation trains a new model to mimic the old model's behavior. Same problem: if the old model learned brittle patterns, you're distilling brittleness.

How training data quality determines what survives

I've traced dozens of catastrophic forgetting incidents back to their source data. The pattern is consistent: what gets forgotten first wasn't solidly learned in the first place.

A model "forgets" how to handle edge cases in contract analysis because the original training set had three examples of indemnification clauses, all from the same legal jurisdiction. The model learned a brittle pattern that appeared to understand during evaluation but collapsed under the distributional shift of new training.

We tested this directly. One client's initial training set of 800 examples produced 91% accuracy. After fine-tuning on a new category, accuracy on original categories dropped to 76%.

A senior data scientist audited the 800 examples. She found the coverage gaps within an hour — document subtypes with only 4-6 examples each, all from the same formatting template. The model had learned to recognize templates, not content.

I reconstructed the training set with better distribution: fewer examples overall, but covering more variation. The rebuilt model reached only 87% accuracy initially, but after fine-tuning, it retained 84% on original categories. The knowledge was more robust because it was built on representations that captured actual diversity.

You can't forget what you never really learned. You can only lose the illusion that you knew it.

Why synthetic data makes forgetting worse

When teams can't get enough human-annotated examples, they generate training data synthetically. The reasoning seems sound: if you lack edge case examples, have an AI generate them.

Synthetic data amplifies the problem. We tested this with a document classification model. The team augmented 500 human-labeled examples into 50,000 synthetic variations. Initial accuracy looked strong. But after fine-tuning on a new document type, accuracy on original categories collapsed faster than it did for a model trained on the 500 originals alone.

The synthetic examples had amplified surface patterns, making the model more fragile. Human-curated examples encode judgment about what matters. Synthetic examples encode statistics about what's common. When the distribution shifts — which is exactly what happens during fine-tuning — only the judgment survives.

What this means for training decisions

Every training example you add becomes a permanent constraint on what your model can learn next. The first 10,000 examples aren't just creating initial capabilities, they're defining the baseline you'll need to maintain in every future version.

If those examples are high quality (clear, consistent, representative), they make future iterations easier. The model builds robust representations that survive fine-tuning. If they're noisy or have coverage gaps, you're carrying that forward indefinitely. Each improvement requires compensating for previous weaknesses.

Quality compounds. Three expertly annotated examples that span actual decision boundaries outperform twenty random samples; not just in initial accuracy, but in how the model handles subsequent training. High-quality examples generate gradients that point toward generalizable patterns. Noisy examples generate gradients that point toward artifacts and annotator inconsistencies.

The annotator's understanding becomes the model's resilience. Did they recognize which variations mattered? Did they know why one document subtype differed from another? That judgment determines whether the model builds representations worth preserving or scaffolding that collapses the moment you train on something new.

Contribute to AI training at DataAnnotation

The training decisions that prevent catastrophic forgetting—choosing the right data mix, identifying coverage gaps, recognizing when quality matters more than volume—require human judgment that no automated pipeline replicates. As models grow more capable, the expertise gap widens between teams that understand how training decisions compound and those that don't.

The contributors shaping these systems aren't just labeling data. They're making the quality distinctions that determine whether a model accumulates knowledge or churns through it.

Over 100,000 remote workers contribute to this infrastructure. Getting started takes five steps:

- Visit the DataAnnotation application page and click "Apply"

- Fill out the brief form with your background and availability

- Complete the Starter Assessment—it tests critical thinking, not checkbox compliance

- Check your inbox for the approval decision (typically within a few days)

- Log in to your dashboard, choose your first project, and start earning

No signup fees. DataAnnotation stays selective to maintain quality standards. The Starter Assessment can only be taken once, so read instructions carefully before submitting.

Apply to DataAnnotation if you understand why quality beats volume in advancing frontier AI — and have the expertise to contribute.

.jpeg)