Yes, you can generate code using generative AI. GitHub Copilot, ChatGPT, Claude, and dozens of other tools will write functions, refactor legacy code, and scaffold entire applications. The capabilities are real.

What the demos don't show: the authentication function that passed all tests but silently leaked session tokens to logs for three months. The pricing calculation that handled basic cases perfectly but broke on promotional codes. The database query that worked fine until the table grew past 10,000 rows.

The models reliably generate code that runs. Whether that code is correct, secure, and maintainable depends entirely on factors the capability demos don't address—and that most developers learn the hard way.

This article covers what AI code generation actually delivers, where it breaks, and how to use it without creating problems you'll spend months debugging.

Where does AI code generation work and where does it fail?

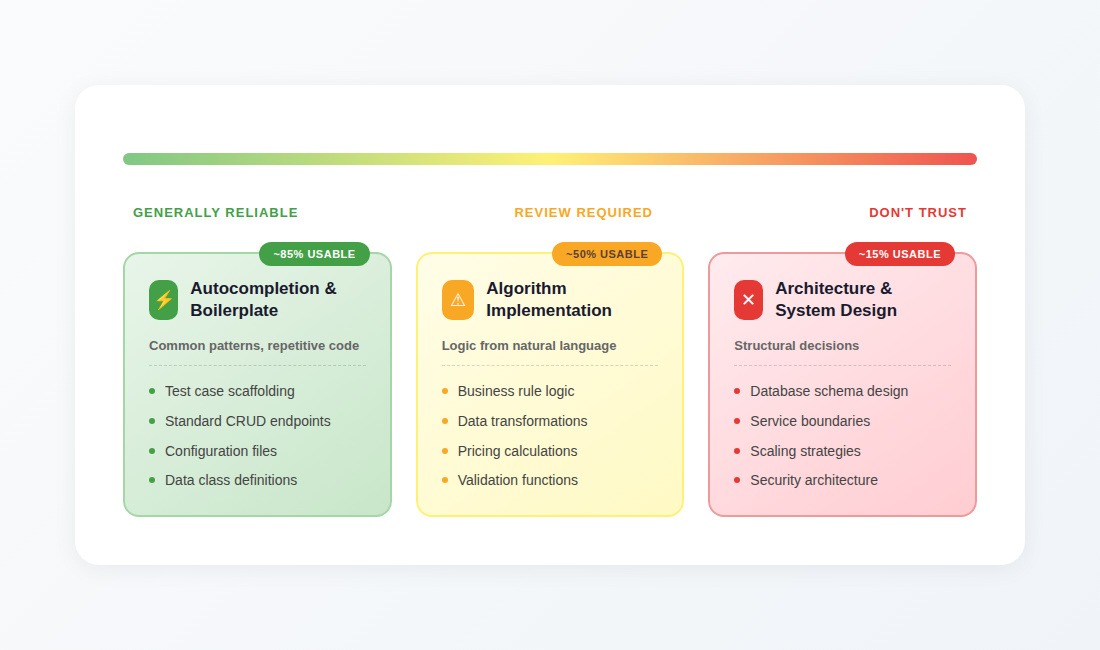

Not all code generation is equally reliable. The same model that writes perfect boilerplate will confidently produce architectural decisions that become six-month cleanup projects.

Autocompletion and boilerplate: generally reliable

This is where models perform best. Test case scaffolding, standard CRUD endpoints, configuration files, data class definitions; these are patterns the model has seen thousands of times in training data.

The model is essentially doing sophisticated retrieval: finding similar patterns from its training corpus and adapting them to your context. When patterns are common enough, this works surprisingly well. Developers report significant acceleration on repetitive tasks, and the error rate is low enough that quick review catches most issues.

Advice: Use freely, review quickly.

Algorithm implementation: Review required

Accuracy drops when you're asking the model to implement logic from natural language descriptions. For well-known algorithms, such as sorting, searching, standard data transformations, or BFS and DFS graph traversals, results are usually reasonable. For anything involving domain-specific rules or unusual requirements, generated code handles obvious cases and fails on everything else.

A pricing calculation function is a typical example. It handles base price correctly and single discounts correctly. It breaks when promotional codes interact with bulk discounts interact with regional pricing adjustments. The model generates code that works for the cases that appear most frequently in training data and fails on the edge cases that define real business logic.

Advice: Generate, but verify edge cases thoroughly before trusting.

Architecture and system design: don't trust

This is where models are weakest and most dangerous. They produce code that follows architectural patterns they've seen, but they lack contextual understanding to make appropriate tradeoffs.

Systems get designed for the wrong scale. Abstractions create bottlenecks that only appear under load. Component structures make future changes difficult in ways that take months to recognize. The model optimizes for patterns that looked good in training examples without understanding why those patterns existed or whether they apply to your situation. Anyone who's prepared for system design interviews knows these decisions require understanding constraints that models can't infer from a prompt.

Advice: Use for brainstorming only. Make structural decisions yourself.

The gap between "working" and "correct"

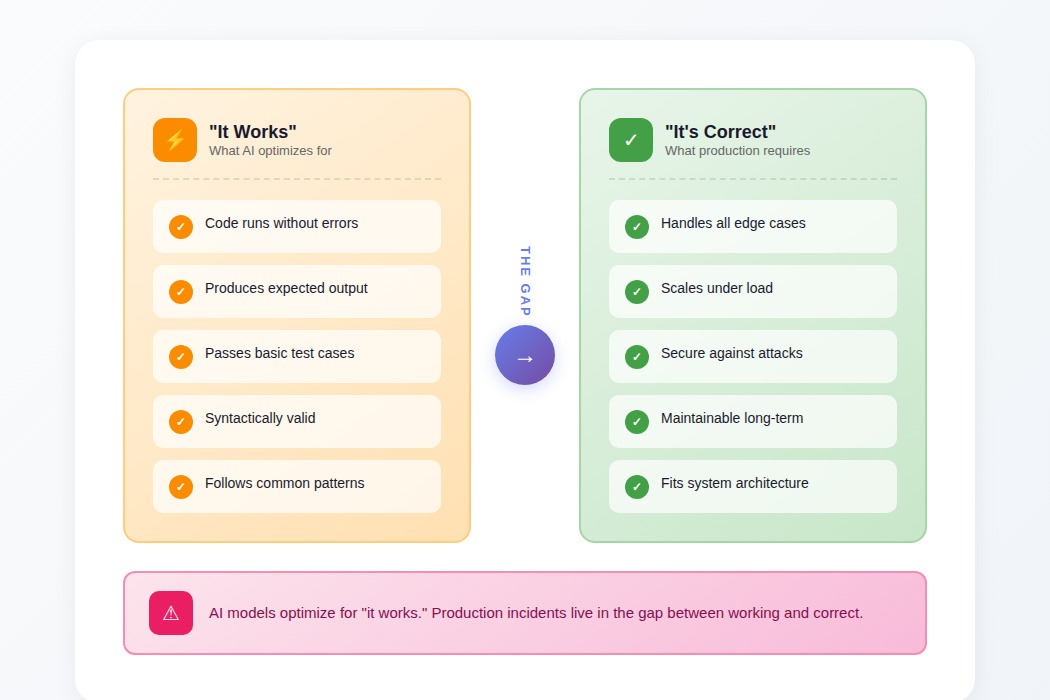

The fundamental issue with AI-generated code isn't that it fails obviously, it's that it succeeds superficially.

"It runs" and "it's correct" are different standards, and models optimize for the former without understanding the latter. When generated code executes on the first try, the natural assumption is that it works. The problems emerge later: in edge cases nobody tested, under load nobody simulated, during security reviews months after deployment.

A date parsing function that handles ISO formats but breaks on RFC 2822. An API client that works until rate limits hit. A caching layer that functions perfectly but bypasses the audit logging that compliance requires. The code does what it says. The problem is that what it says isn't what the system needs.

This creates a specific kind of technical debt: code that works well enough to ship but poorly enough to break later, written by a process that didn't understand the requirements it was supposedly implementing.

Why models fail: the mechanisms worth understanding

Understanding how these failures happen helps predict when they'll occur.

Pattern matching, not reasoning

These models predict tokens based on patterns learned from billions of lines of code. When prompted to write a sorting algorithm, the model isn't reasoning about time complexity or memory allocation. It's generating text that statistically resembles code it's seen in similar contexts — a form of in-context learning that mimics understanding without possessing it.

This works well for common patterns: the model has seen thousands of REST endpoints, so it generates reasonable REST endpoints. It breaks for anything outside the training distribution. When the model generates if (x = 5) instead of if (x == 5) in JavaScript, the error is statistical: both patterns exist in training data, and the model picked the wrong one. It has no internal concept of "assignment versus comparison" to catch the mistake.

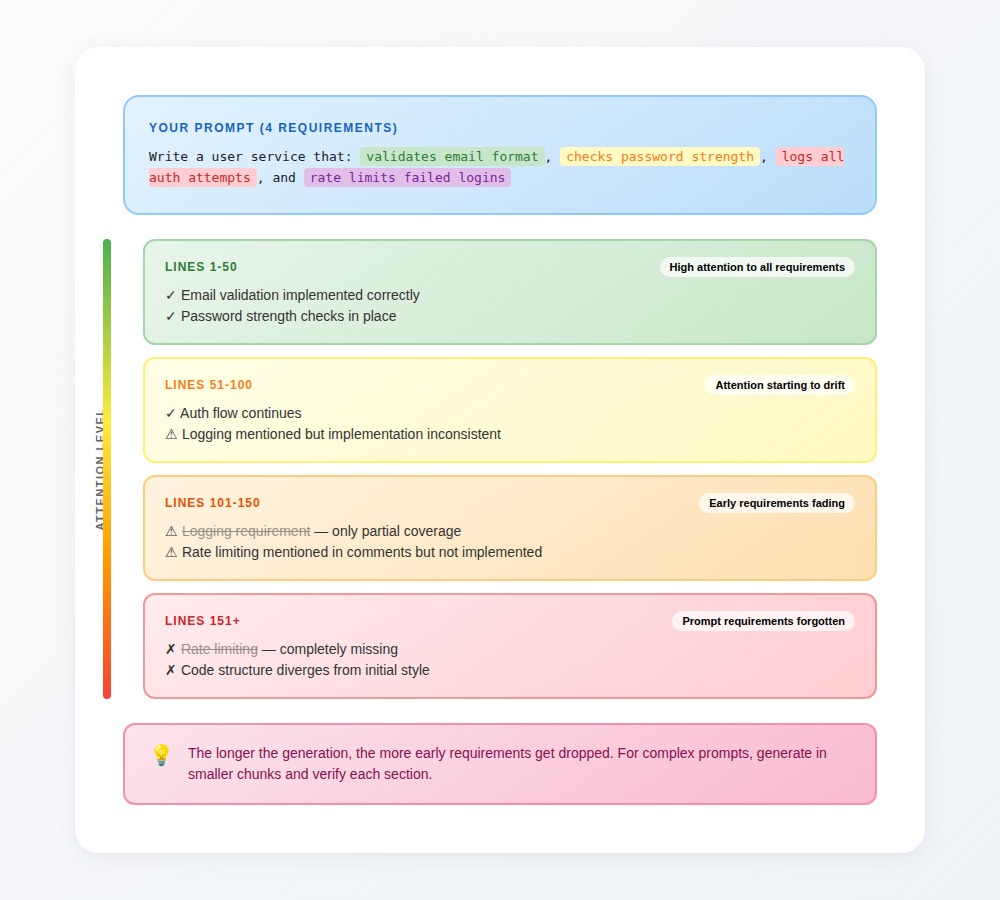

Context window degradation

Every model has a finite context window, and attention degrades as generation continuesThe further into a response the model generates, the less attention it pays to early parts of the prompt.

For long generations, this manifests as dropped requirements. You specify four constraints in your prompt; by line 150, the model has forgotten two of them. Error handling specified early gets omitted entirely. Style drifts gradually as the model loses track of initial patterns. Requirements mentioned at the beginning of a complex prompt have measurably lower compliance by the end of generation.

Hallucinations: confident nonsense

The most unnerving failure mode: code that looks perfectly plausible but can't possibly work.

Models generate imports for packages that don't exist but sound like they should. They use API methods that were never implemented. They combine features from different library versions in ways that were never compatible. They reference configuration options that match the pattern of real options but aren't supported.

The code compiles in the model's imagination. It doesn't compile in reality.

Training data cutoffs and outdated patterns

Every few weeks, developers get frustrated that a model suggested a deprecated API or an authentication pattern with known vulnerabilities patched months ago.

The deeper problem: models generate outdated code with the same confidence as current recommendations. Nothing in the output signals that a suggestion is stale. The model suggests deprecated packages, abandoned frameworks, and security patterns that maintainers explicitly advise against, all presented as if they're standard practice.

How to use AI code generation

The failure modes are predictable. That means they're avoidable with the right workflow.

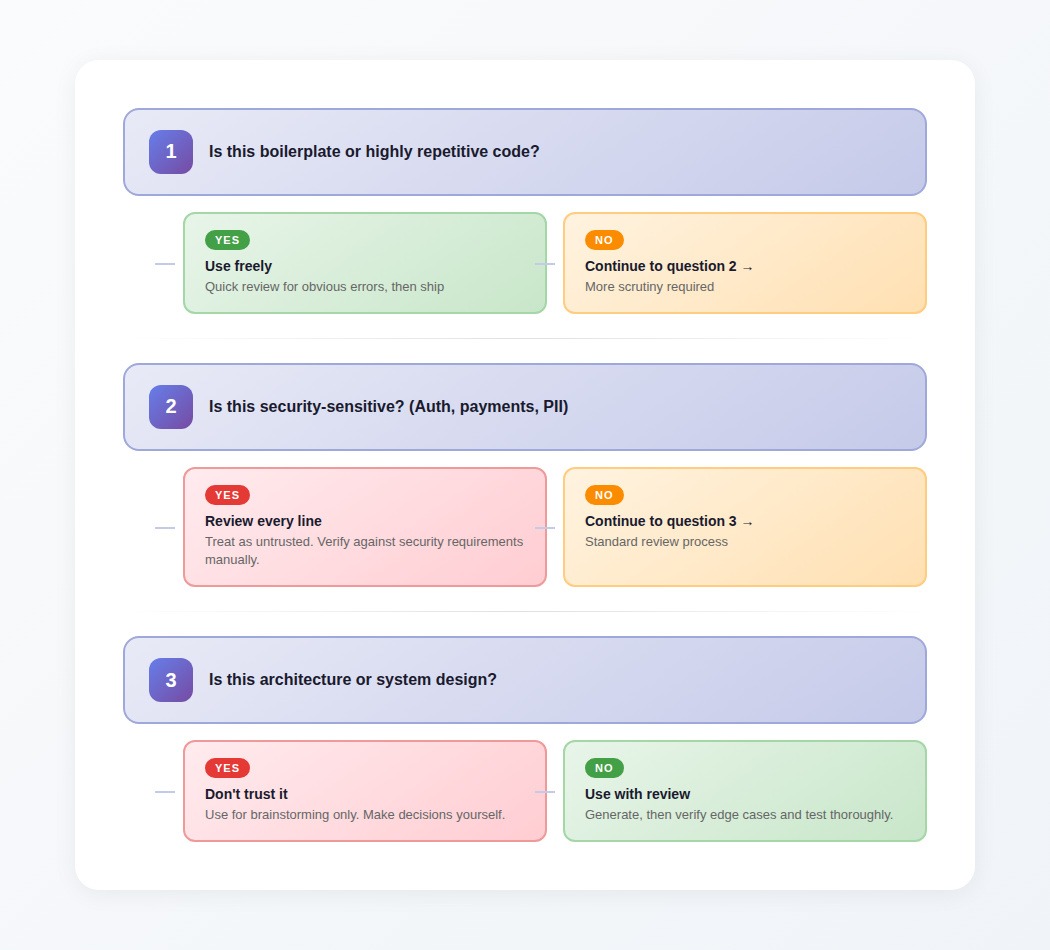

Match trust level to code type

Use freely: Boilerplate, test scaffolding, configuration files, data classes, standard patterns you'd write the same way every time.

Use with careful review: Business logic, data transformations, API integrations, anything involving conditional logic or edge cases.

Use for brainstorming only: Architecture decisions, database schema design, security-sensitive code, performance-critical paths.

Prompt for verification, not just generation

The difference between useful and dangerous AI code generation often comes down to how you prompt.

Weak prompt: "Write a function that validates email addresses"

Better prompt: "Write a function that validates email addresses. Include handling for: empty input, strings without @ symbol, multiple @ symbols, domain validation. Add comments explaining each validation step. Include test cases that verify each edge case."

The second prompt generates code that's easier to review because it forces the model to be explicit about what it's handling. You can immediately see what's missing.

Generate in chunks, not monoliths

Long generations degrade. Instead of prompting for an entire module, generate function by function. Verify each piece works before moving to the next. This catches context window drift before it compounds.

For complex features: prompt for the interface first, verify it makes sense, then prompt for implementation of each method separately. The overhead is worth it compared to debugging a 500-line generation where requirements got dropped somewhere in the middle.

Treat generated code as untrusted input

Every piece of generated code should go through the same review you'd give code from a new hire you don't fully trust yet. Read it. Understand it. Don't merge code you can't explain.

Specific review checklist for generated code:

- Do you understand what every line does?

- Are edge cases handled, or just the happy path?

- If security-sensitive: have you traced all data flows manually?

- Does it match your codebase's patterns, or introduce inconsistencies?

- Can you explain why it's implemented this way?

If you can't answer these, don't ship it.

Test more aggressively than usual

Generated code passes the tests you write for it. It doesn't pass the tests you don't think to write.

For AI-generated code, specifically test:

- Boundary conditions (empty input, one item, max values)

- Error paths (what happens when dependencies fail?)

- Concurrency (what if this runs twice simultaneously?)

- Scale (does this work with 10x the data? Will you hit database deadlocks under load?)

The model is optimized for patterns, not correctness. Your tests are the only verification that it got correctness right.

The maintainability problem: technical debt you can't see

Short-term, AI code generation feels like acceleration. Long-term, the maintainability costs compound.

Code without context

When developers write complex algorithms, they typically leave comments explaining non-obvious decisions; the reasoning that would be lost if only the code existed. AI-generated code rarely includes this context because the model doesn't have it. The reasoning that would normally live in commit messages, PR descriptions, and inline comments simply doesn't exist.

Three months later, when the code needs modification, nobody can explain why it works the way it does. The implementation decisions that seemed arbitrary were probably arbitrary; the model picked one of several valid patterns without understanding why. Changing it safely requires understanding the model never had.

Non-idiomatic patterns

Every codebase develops conventions: how errors propagate, how resources are managed, how components interact. AI models don't internalize your team's patterns. They generate code reflecting patterns from training data, which may have nothing to do with how your team builds software.

The maintenance cost compounds because non-idiomatic code is harder to modify correctly. When you change how a system handles database connections, you need to update all code that interacts with the database. If that code follows consistent patterns, changes are mechanical. When half the database-touching code follows different patterns because AI generated it, each change requires careful analysis.

The documentation gap

Generated code creates documentation debt. The model produces implementation, not explanation. When onboarding new developers or debugging production issues, the missing context becomes costly.

Teams that use AI code generation sustainably build documentation into their workflow: require comments explaining non-obvious decisions, write commit messages that capture intent, maintain architecture documents that explain why systems are structured as they are. The generation is fast; the documentation is where actual effort goes.

Why this matters: training data shapes model capability

The failure modes described above aren't random. They trace directly to what models learned during training and what they didn't.

A model that consistently suggests deprecated functions learned from training data that treated those functions as current. A model that generates SQL injection vulnerabilities learned from examples where those patterns appeared without correction. A model that produces code handling common cases but failing on edge cases learned from datasets that emphasized common patterns over comprehensive coverage.

The quality ceiling for any code generation model is the quality of examples it learned from. Feed a model thousands of examples where error handling is absent, it learns that error handling is optional. Train it on code without comments explaining non-obvious decisions, it learns that such comments aren't necessary.

This is why high-quality training data for code generation requires human expertise: developers who can identify why specific outputs fail, what patterns the model misunderstands, and what edge cases the training examples didn't cover. The evaluation work that shapes better models requires exactly the judgment skills that make someone a good code reviewer—distinguishing code that works from code that's correct.

Contribute to AI development at DataAnnotation

The code generation models reshaping software development depend entirely on the quality of human evaluation in their training. When a model suggests the right refactoring rather than plausible-but-wrong syntax, when it handles edge cases rather than just the happy path, that capability traces directly to human expertise that identifies what "correct" actually means.

The same judgment that catches problems in code review — distinguishing superficially working code from genuinely correct implementations — is exactly what's valuable in AI training.

Technical expertise, domain knowledge, or critical thinking skills all position you well for AI training at DataAnnotation. Developers looking for part-time work that actually uses their technical judgment, rather than abandoning it for generic gig tasks, find code evaluation particularly well-suited to their skills. Over 100,000 remote workers have contributed to this infrastructure.

Getting started takes five steps:

- Visit the DataAnnotation application page and click "Apply"

- Fill out the brief form with your background and availability

- Complete the Starter Assessment—it tests critical thinking, not checkbox compliance

- Check your inbox for the approval decision (typically within a few days)

- Log in to your dashboard, choose your first project, and start earning

No signup fees. DataAnnotation stays selective to maintain quality standards. The Starter Assessment can only be taken once, so read the instructions carefully before submitting.

Apply to DataAnnotation if you understand why judgment beats pattern-matching: in code review, in AI-generated code evaluation, and in training the models that developers will rely on.

.jpeg)