A deployment failed last month because a developer swapped HashMap for TreeMap to "get sorted keys." The code compiled. Tests passed. Then latency spiked 300% on the highest-traffic endpoint. The sorted keys were never even used.

Both implementations satisfied the Map interface. Both honored the abstract data type contract. But the underlying data structures carried fundamentally different costs—and that difference broke production.

This confusion between abstract data type and data structure surfaces constantly in production systems. One is a promise. The other is a performance characteristic. Conflate them and you build systems that work perfectly until they don't.

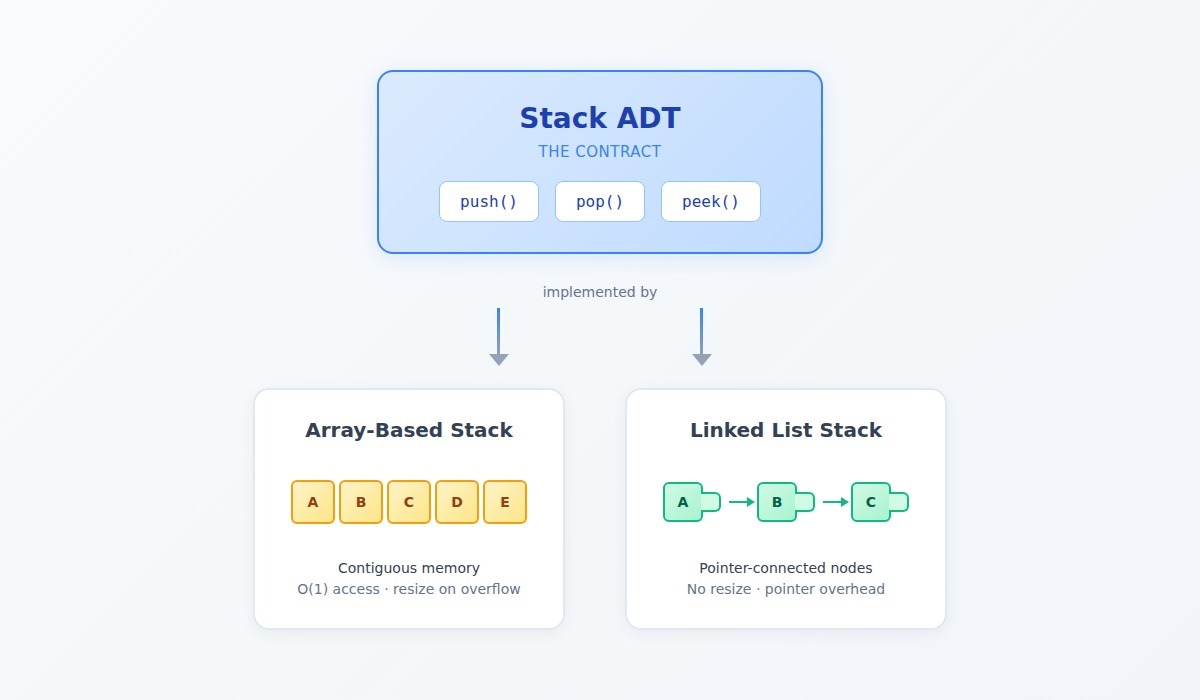

What is an abstract data type?

An abstract data type specifies the operations available on a data type and the behavior those operations guarantee. The specification says nothing about memory layout, pointer manipulation, or algorithmic complexity.

Consider the Stack ADT:

- push(element): Add an element to the top

- pop(): Remove and return the top element

- peek(): View the top element without removing it

- Behavior guarantee: Last-in-first-out (LIFO) ordering

The Stack ADT makes no promises about whether push runs in O(1) or O(n) time. That's an implementation detail the abstraction deliberately hides.

Common abstract data types include:

- List: Ordered sequence with index-based access

- Map/Dictionary: Key-value associations with key-based retrieval

- Set: Collection of unique elements with membership testing

- Queue: First-in-first-out ordering

- Priority Queue: Ordering by priority value

Each ADT defines a contract: the operations clients can depend on and the behavioral guarantees they receive. The contract protects calling code from implementation changes.

What is a data structure?

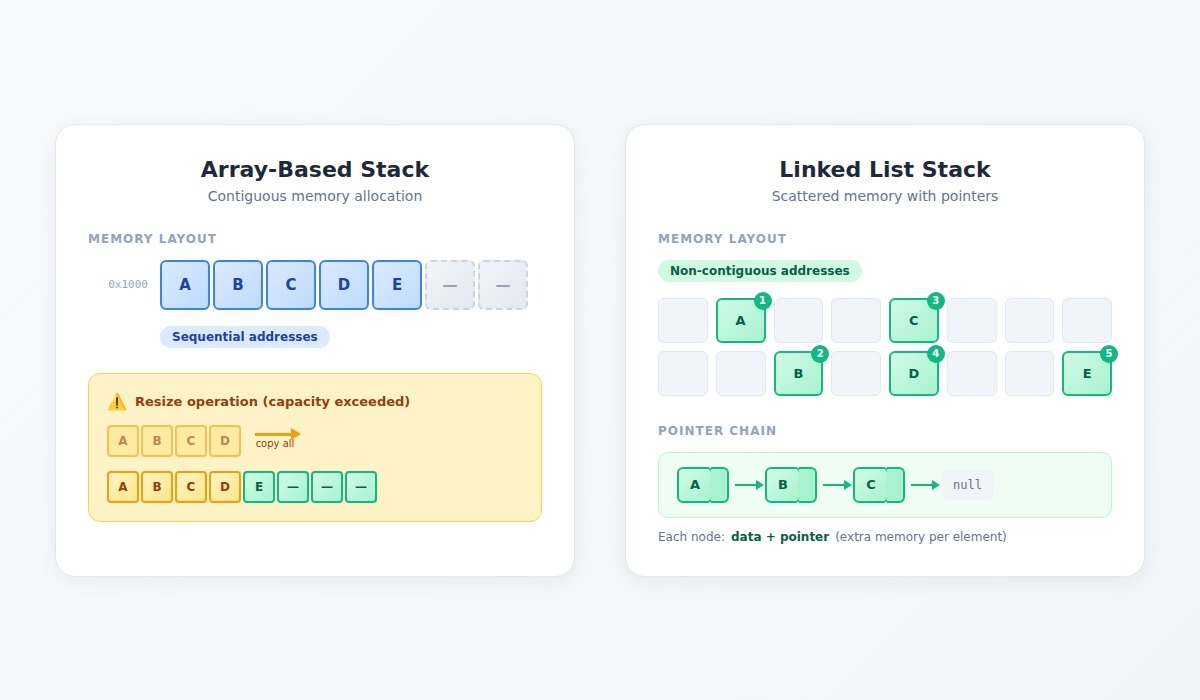

A data structure is the concrete implementation that makes an ADT's operations work. It specifies memory layout, pointer relationships, and the algorithms that execute each operation.

Consider two data structures that implement the Stack ADT:

Array-based stack: Stores elements in contiguous memory. Push appends to the end; pop removes from the end. Indexed access is O(1). But when the array fills, resizing requires copying every element to new memory.

Linked-list stack: Stores elements as nodes with pointers. Push creates a new node and updates the head pointer. Pop updates the head and returns the old node's value. No resizing, but each node carries pointer overhead.

Both satisfy the Stack ADT contract. Both deliver LIFO behavior. But their performance characteristics differ dramatically depending on access patterns.

Key differences between ADT and data structure

The ADT answers: "What can this type do?" The data structure answers: "What does it cost?"

Why the distinction matters

The ADT is your contract, while the data structure is your optimization. Confuse them and you either paint yourself into implementation corners or build dependencies on behavior that was never guaranteed.

Contract vs optimization

The ADT represents the contract that the calling code depends on. The data structure represents the optimization chosen for specific constraints. Conflating the two creates fragile systems.

A deployment failed last month because a developer swapped HashMap for TreeMap to "get sorted keys." The Map ADT makes no ordering promises. The developer assumed that because both implemented Map, they were interchangeable. Production latency spiked 300% on the highest-traffic endpoint. The sorted keys were never used.

The Map ADT contract held. The performance assumption broke.

Implementation changes that violate implicit guarantees

Training data for AI systems encodes assumptions about data structure behavior. When teams build classification models using examples generated from Python's default dictionary (which maintains insertion order since Python 3.7), the model learns patterns that assume stable iteration order. Deploy that model against a distributed key-value store with no ordering guarantees, and those patterns break.

The model doesn't fail completely. It degrades subtly as the input distribution shifts away from training conditions. The dictionary ADT contract was satisfied. The implementation detail the model depended on changed.

This problem surfaces constantly in production ML systems. A document processing model trained on examples from one queue implementation learned timing patterns specific to that implementation's ordering behavior. When the production environment used a different queue, those patterns became noise. Accuracy dropped from 89% to 61% over three weeks as the distribution drift compounded.

Performance characteristics that cascade through systems

One team built a task scheduler using an unsorted array to implement the Priority Queue ADT. Insert was O(1); extract-max was O(n). With 50 tasks in testing, this worked fine. Production scaled to 10,000 concurrent tasks. Extract-max became a 10,000-operation scan executed thousands of times per minute. The scheduler ground to a halt.

Switching to a binary heap implementation changed extract-max from 10,000 operations to roughly 13. Same ADT, same interface, same calling code. The data structure choice determined whether the system functioned at scale.

Training data organization affects learning dynamics

Model architectures encode assumptions about data access patterns. A code completion model organized training data as nested dictionaries keyed by repository, then file, then function. Clean abstraction, sensible hierarchy. The problem emerged during training: the data loader performed O(n) scans through repository dictionaries to find each batch. First epoch took 11 hours. Restructuring to a flat array with index mappings dropped epoch time to 47 minutes.

Transformers need contiguous memory blocks for GPU parallelization. When data structure choices fight against hardware access patterns, every training step pays that cost. Also, beyond raw performance, data structure affects what models learn.

Common examples that clarify the difference

Let’s take a look at some common instances that make a clear distinction between ADTs vs data structures:

Stack: Array vs linked list implementation

A content moderation system needed to track nesting depth in JSON structures. The initial implementation used a dynamic array: push appended to the end, pop removed from the end. Standard choice for most use cases.

Production traffic included deeply nested structures. Fifteen levels deep. The array-based stack resized constantly. Each resize allocated new memory and copied every element. With thousands of concurrent parsing operations, memory allocation became the bottleneck. Throughput dropped 40%. Garbage collection pauses compounded the problem as discarded arrays accumulated.

Switching to a linked-list implementation of the same Stack ADT eliminated resize operations entirely. Each push allocated a single node. Each pop freed a single node. Same three operations, same LIFO semantics, zero code changes in parsing logic. Throughput recovered.

The reverse happens too. A logging system used a linked-list stack because "stacks should be linked lists." The access pattern involved frequent iteration through recent entries for correlation analysis. Linked lists scatter nodes across memory with poor cache locality. Every node access meant a potential cache miss. Switching to an array-based stack cut processing time 60% because modern CPUs prefetch sequential memory efficiently.

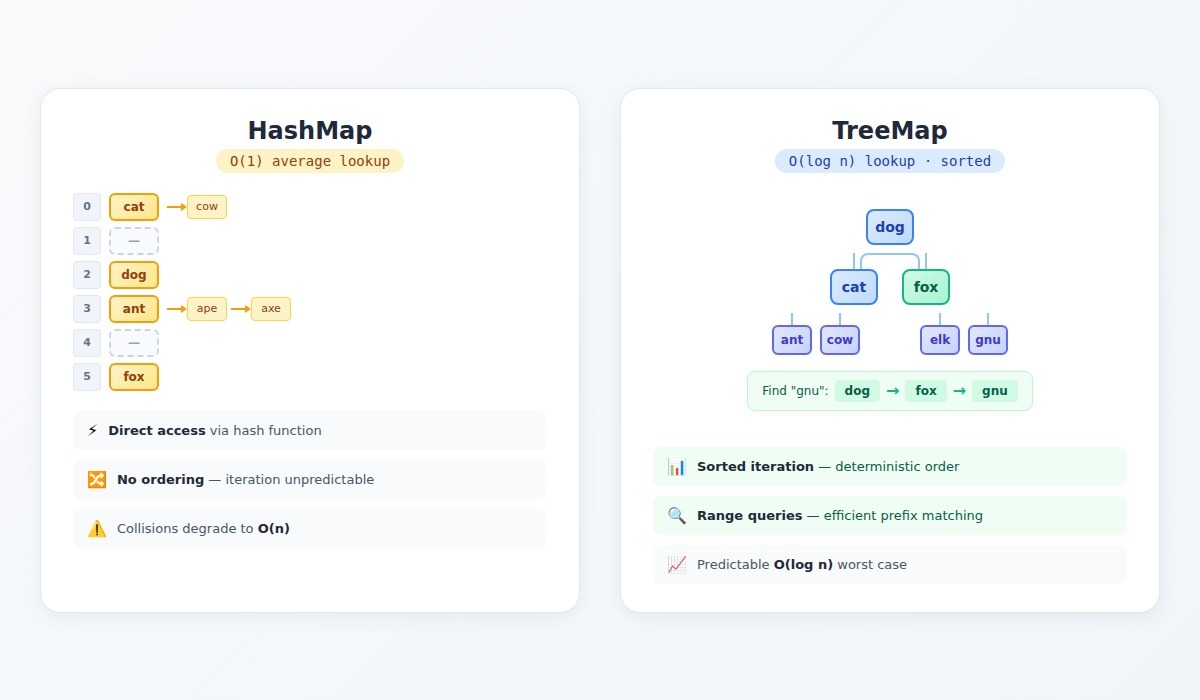

Map: HashMap vs TreeMap

The Map ADT promises key-value associations and key-based retrieval. Implementation choices determine everything else.

- HashMap: Array of buckets with collision chains. Average O(1) lookup. Undefined iteration order. Memory-efficient for large collections when hash distribution is good. Performance degrades to O(n) with poor hash functions or adversarial inputs.

- TreeMap: Balanced binary tree. O(log n) lookup. Sorted iteration order. Efficient range queries. Predictable worst-case performance. Higher memory overhead per entry due to tree node structure.

A feature flag system for AI training pipelines initially used HashMap. Fast lookups worked well. But the team needed consistent flag ordering across distributed workers for reproducibility. Different workers iterating through the same HashMap in different orders produced non-deterministic training runs. Debugging became impossible.

They also needed prefix matching: "enable all flags starting with tokenizer_." HashMap requires scanning every key for prefix matches: O(n). TreeMap's sorted structure enables efficient range queries: O(log n + k) where k is the number of matching results.

TreeMap solved both problems. Sorted iteration became deterministic. Prefix queries ran efficiently. With 100 flags, lookup slowed from one operation to seven. Imperceptible in context. The trade-off was worth the guarantees.

Priority Queue: Unsorted array vs binary heap

The Priority Queue ADT promises insertion and extraction of the highest-priority element. The implementation determines whether those operations scale.

- Unsorted array: O(1) insert, O(n) extract-max. Simple. Works for small collections.

- Binary heap: O(log n) insert, O(log n) extract-max. More complex. Scales to millions of elements.

A distributed annotation job scheduler used the unsorted array approach. Testing with 50 tasks showed no problems. Production with 10,000 tasks turned extract-max into a performance disaster. The binary heap implementation made the scheduler viable.

Contribute to AGI development at DataAnnotation

The separation between interface contracts and implementation details is evident throughout AI systems. Evaluating whether a model learned abstract patterns versus memorized specific implementations requires exactly this kind of analytical distinction.

If your background includes technical expertise, domain knowledge, or the critical thinking to evaluate complex trade-offs, AI training at DataAnnotation positions you at the frontier of AGI development.

Over 100,000 remote workers have contributed to this infrastructure.

If you want in, getting from interested to earning takes five straightforward steps:

- Visit the DataAnnotation application page and click "Apply"

- Fill out the brief form with your background and availability

- Complete the Starter Assessment, which tests your critical thinking skills

- Check your inbox for the approval decision (typically within a few days)

- Log in to your dashboard, choose your first project, and start earning

No signup fees. We stay selective to maintain quality standards. You can only take the Starter Assessment once, so read the instructions carefully and review before submitting.

Apply to DataAnnotation if you understand why quality beats volume in advancing frontier AI — and you have the expertise to contribute.

Frequently asked questions

Is an array a data structure or an ADT?

An array is typically a data structure: a concrete implementation with specific memory layout (contiguous storage) and performance characteristics (O(1) indexed access, O(n) insertion in the middle). The List ADT might be implemented using an array, but the array itself is the implementation, not the abstraction.

Can one data structure implement multiple ADTs?

Yes. A balanced binary search tree can implement the Set ADT (unique elements, membership testing), the Map ADT (key-value pairs), and aspects of the Priority Queue ADT (efficient min/max extraction). The same underlying structure serves different abstract purposes.

Why not just specify performance in the ADT?

Some languages and libraries do specify complexity guarantees as part of the interface. Java's SortedMap interface implies O(log n) operations. But separating behavior from performance allows implementations to optimize for different constraints. An ADT that mandates O(1) lookup can't be implemented with a tree structure, even when sorted iteration matters more than lookup speed.

What is the difference between ADT and data type?

A data type is a classification that specifies what values a variable can hold (integer, string, boolean). An abstract data type goes further: it specifies both the possible values and the operations that can be performed on those values, along with behavioral guarantees. The integer data type tells you a variable holds whole numbers. A Counter ADT tells you the operations available (increment, decrement, get) and their behavior (increment adds one, decrement subtracts one, value never goes negative).

Is a linked list an ADT or data structure?

A linked list is a data structure. It specifies a particular implementation: nodes connected by pointers. The List ADT defines operations like add, remove, and get-by-index. A linked list is one way to implement the List ADT; an array is another. The linked list's specific properties (O(1) insertion at known positions, O(n) indexed access, pointer overhead per element) are implementation characteristics the List ADT deliberately leaves unspecified.

How does this apply to AI training data?

Training data organization is a data structure decision with direct impact on learning dynamics. The same abstract dataset can be stored in a hash table (random access) or a sorted array (curriculum learning from simple to complex). The structure changes gradient updates the model encounters, which changes what patterns it learns. Models trained on identically labeled data can reach different accuracy levels based purely on how that data is organized and accessed during training.

.jpeg)