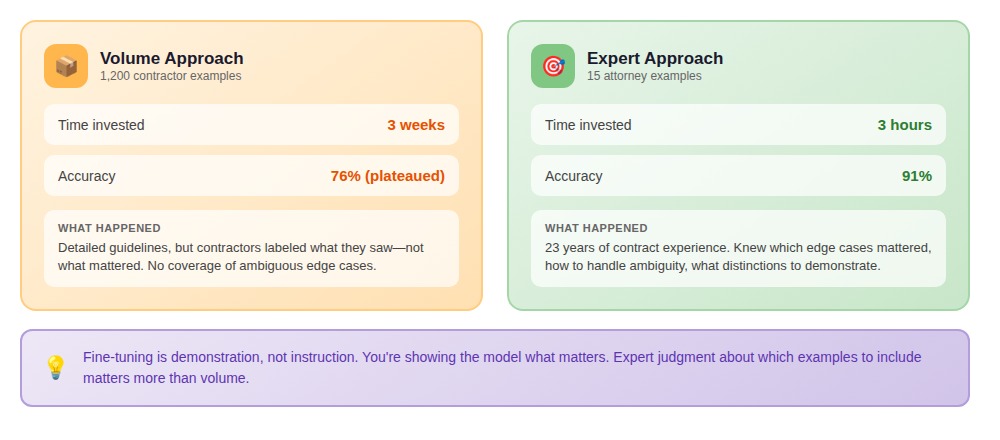

A legal tech company ran a parallel experiment on contract clause extraction.

One team: offshore contractors labeling 1,200 examples over three weeks using detailed guidelines. The other: a senior contracts attorney with 23 years of negotiating commercial agreements, spending three hours crafting 15 examples.

The contractors' model plateaued at 76% accuracy. The attorney's model hit 91%.

This is what transfer learning promises: democratization. Pre-train a massive model once, then let anyone fine-tune it with minimal data. Training a state-of-the-art image classifier from scratch requires millions of labeled examples and weeks of GPU time. With transfer learning: thousands of examples and days of fine-tuning, at a fraction of the cost.

What the success stories gloss over is that transfer learning doesn't eliminate the complex parts of machine learning, it shifts them. You're no longer solving "how do I teach a model to recognize patterns from nothing?" You're solving "how do I adapt someone else's learned patterns without breaking what works or encoding what doesn't apply?"

Understanding why 15 expert examples outperformed 1,200 requires understanding what transfer learning actually does and what it leaves for you to solve.

What is transfer learning?

Transfer learning is a machine learning technique where a model trained on one task is repurposed as the starting point for a different task. Instead of training from scratch with randomly initialized weights, you start with a model that has already learned useful representations from a larger dataset.

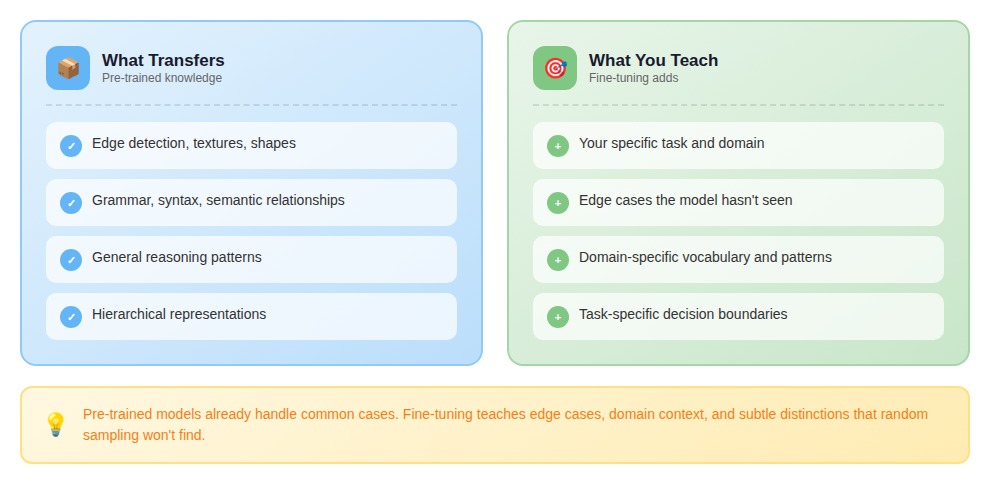

A model trained on millions of photographs has learned general visual principles: edges, textures, shapes, spatial relationships. When you build a medical imaging classifier or manufacturing defect detector, you don't need to teach the model what an edge is, you teach it what your specific problem looks like, building on foundations already laid.

A model trained on billions of words has learned grammar, syntax, semantic relationships, and reasoning patterns. Fine-tune it on legal document analysis or customer support classification, and you inherit that foundation rather than building from nothing.

Why transfer learning works

Neural networks learn hierarchical representations. Early layers detect basic features: edges, textures, simple patterns. Middle layers combine these into more complex structures. Deeper layers assemble high-level concepts.

These representations aren't task-specific. The edge detector that identifies cats also identifies tumors in X-rays. The texture analyzer trained on natural images transfers to satellite imagery or manufacturing defects. This is why a retinal imaging team doesn't need millions of examples. The model arrives already understanding visual structure. Fine-tuning teaches "here's what diabetic retinopathy looks like" without relearning "here's what an edge is."

In computer vision, ResNet, VGG, and EfficientNet trained on ImageNet's 14 million images became the starting point for almost everything: medical imaging, satellite analysis, manufacturing QC, autonomous vehicles. Training from scratch became the exception.

In language, the shift was more dramatic. BERT demonstrated that a model pre-trained on massive text corpora could fine-tune for almost any language task. GPT showed models trained to predict the next word could generate text, write code, and reason through problems. Each demonstrated the same principle: learn general representations once at massive scale, then adapt cheaply to specific problems.

What are the different types of transfer learning?

The relationship between your source task (what the model was initially trained on) and target task (what you want it to do) determines which approach works.

Inductive transfer applies when your target task differs from the source task, but you have labeled data for both. A model trained on photographs adapts to detect manufacturing defects. A language model trained on web text fine-tunes for contract analysis. A pathology team used inductive transfer to build a tumor classification system — their base model understood tissue textures and cell boundaries; fine-tuning on 400 slides annotated by an oncology pathologist reduced data requirements by roughly 95% compared to training from scratch.

Transductive transfer addresses domain shift: same task, different distribution. A sentiment classifier trained on product reviews adapts to movie reviews. A fraud detection model trained on one bank's transactions transfers to another bank. The challenge is distribution mismatch — product reviews say "this camera takes great photos" while movie reviews say "the cinematography was stunning." Same sentiment, different vocabulary. When transductive transfer fails, you get confident predictions that are systematically wrong.

What transfers and what doesn't: Lower-level representations transfer reliably — edge detectors, texture analyzers, basic syntactic patterns generalize across tasks. Task-specific decision boundaries, domain vocabulary, and contextual interpretations often need to be relearned.

This is why negative transfer happens. When source and target domains are too dissimilar, pre-trained assumptions actively hurt performance. A model trained on natural images may learn "bright regions indicate foreground objects" — a heuristic that fails on X-rays where bright regions indicate bone. We've seen a document classifier pre-trained on news articles perform worse than a from-scratch model on legal briefs because the news model learned that short paragraphs signal importance — a pattern that inverts in legal writing.

Feature extraction vs. fine-tuning

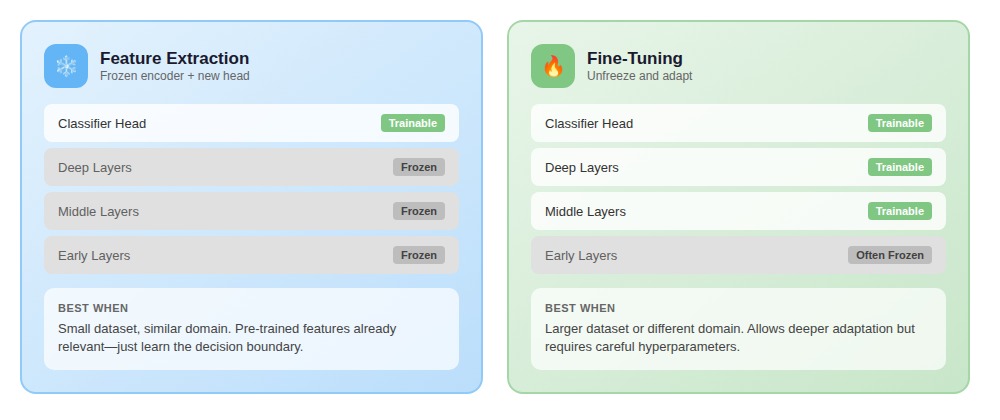

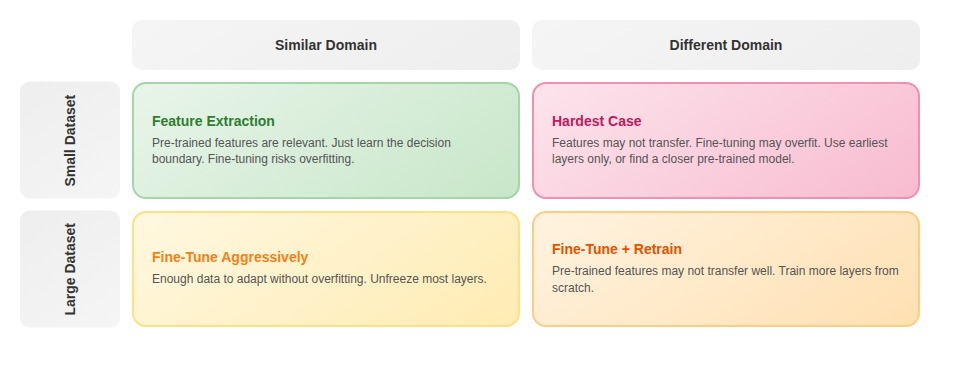

Once you've selected a pre-trained model, you choose how much to adapt.

Feature extraction treats the pre-trained model as a frozen feature generator. Pass data through the network, extract representations, train only a new classifier head. Original weights never change. Best when your target domain matches the source and your dataset is small. A team with only 150 labeled manufacturing defect images extracted features from ResNet-50 and trained a logistic regression classifier — full fine-tuning would have overfit within epochs.

Fine-tuning unfreezes some or all pre-trained layers and continues training on your data. This allows deeper adaptation but requires more data and careful hyperparameters to avoid destroying what the model already knows. A clinical NLP team fine-tuned BERT for extracting diagnoses from physician notes. Feature extraction alone: 74% F1. After unfreezing the top four transformer layers with a learning rate one-tenth of the classifier head: 86% F1. The fine-tuned layers learned how physicians abbreviate conditions, when context changes meaning, and which qualifiers indicate uncertainty versus confirmation.

For large language models, LoRA offers a middle path: training small adapter matrices while keeping base weights frozen, reducing compute requirements while still adapting model behavior.

The decision depends on two factors: how much labeled data you have and how similar your target domain is to the source.

Fine-tuning vs. other adaptation approaches

Fine-tuning isn't the only way to adapt pre-trained models. In-context learning lets you guide model behavior through examples in the prompt itself—no weight updates required. RAG architectures augment models with retrieved knowledge rather than baking information into weights.

Each approach has tradeoffs. In-context learning requires no training but is limited by context window size and adds latency. RAG excels for factual recall but struggles with nuanced judgment. Fine-tuning permanently encodes patterns but requires quality training data and risks degrading base capabilities.

The choice depends on what you're adapting: factual knowledge often suits RAG, behavioral patterns often require fine-tuning, and simple task guidance can work in-context. Many production systems combine approaches.

Why fine-tuning data quality beats volume

Transfer learning reduces data volume requirements. The paradox: it simultaneously increases the expertise required for each example.

When you're working with 50 examples instead of 50,000, each carries exponentially more weight. A single poorly-crafted example can create failure modes that surface unpredictably across thousands of production inputs.

The coverage problem: Pre-trained models already handle common cases. The point of fine-tuning is to teach edge cases, domain-specific contexts, and subtle distinctions. Random sampling doesn't find those patterns.

A financial services team brought us a failing summarization task. Their training set had 100 randomly sampled earnings call transcripts. The model produced fluent summaries but missed forward-looking statements — the specific signal their analysts needed. Only six transcripts contained clear examples of forward-looking language, and labels didn't mark them as important.

We rebuilt with 15 specifically chosen examples: transcripts with forward-looking statements labeled to highlight that language, transcripts with similar-sounding historical discussion labeled to show the distinction. The model fine-tuned on those 15 examples preserved forward-looking language with 90%+ consistency.

The annotation precision gap: Even when critical patterns appear in training data, labels must encode them precisely. A team labeled 50 examples for named entity recognition in legal documents. Labels were technically correct, but the model failed in production because it couldn't distinguish between a party to the contract and a party mentioned in an example clause. The training labels didn't encode that distinction. Expert-crafted examples close this gap because the person creating them understands what distinction matters.

Understanding what distinction matters — that's expertise, not throughput. If you have domain knowledge that lets you encode the right boundaries in training data, we can put that judgment to work. Apply to DataAnnotation.

Model priors amplify quality differences: Pre-trained models come loaded with assumptions. When you fine-tune, you're not writing on a blank slate, you're redirecting existing patterns.

A documentation team fine-tuned BERT for internal search. Initial training set: 40 randomly sampled question-snippet pairs. The model returned plausible results but consistently shallow. It grabbed introduction paragraphs rather than detailed technical content. The model's priors from general web search were dominating.

We rebuilt with eight examples specifically demonstrating the distinction: questions paired with detailed technical snippets, not overviews. Those eight examples created enough signal to redirect the model's priors.

The stronger the model's existing priors, the more precisely you need to craft examples showing how your task diverges. That precision matters far more than volume.

How does transfer learning change AI economics?

Traditional machine learning requires massive labeled datasets for every task. Transfer learning inverts this equation. The expensive part (learning general representations) happens once at massive scale, usually by frontier labs. Training GPT-3 cost an estimated $4.6 million in compute. But once completed, your specific task becomes an incremental fine-tuning problem requiring orders of magnitude less data.

This shift makes entire categories of AI applications economically viable. Problems with naturally small datasets, such as rare diseases, specialized legal documents, or niche manufacturing processes, become tractable.

But here's what teams miss: while you need less data, the quality bar goes up dramatically. Fewer examples carry disproportionate weight. A bad batch doesn't just slow progress, it actively degrades the pre-trained model's capabilities. We've seen models worsen after fine-tuning because examples contained inconsistent labeling or didn't cover critical edge cases.

Fine-tuning is demonstration, not instruction. You're not telling the model what to do, you're showing it what matters and hoping it learns why. The quality of that demonstration determines whether you're building systems capable of genuine reasoning or systems that mimic its appearance.

Contribute to AI training at DataAnnotation

Transfer learning accelerates model development by inheriting learned representations. But the quality of that inheritance depends entirely on training data quality and human expertise in evaluation.

As transfer learning democratizes access to powerful base models, the competitive advantage shifts to organizations that understand what makes fine-tuning data genuinely useful rather than superficially adequate. The models are increasingly commoditized. The training data and evaluation expertise that effectively adapt them are not.

Over 100,000 remote workers contribute to this infrastructure. Getting started takes five steps:

- Visit the DataAnnotation application page and click "Apply"

- Fill out the brief form with your background and availability

- Complete the Starter Assessment—it tests critical thinking, not checkbox compliance

- Check your inbox for the approval decision (typically within a few days)

- Log in to your dashboard, choose your first project, and start earning

No signup fees. DataAnnotation stays selective to maintain quality standards. The Starter Assessment can only be taken once, so read instructions carefully before submitting.

Apply to DataAnnotation if you understand why quality beats volume in advancing frontier AI and have the expertise to contribute.

.jpeg)