A fraud detection model hit 92.2% accuracy in testing. Two weeks after deployment, it cost $2 million in false positives.

The team had implemented textbook regularization: L2 penalties, dropout, and early stopping. None of it mattered. The model had memorized noise so thoroughly that no constraint could save it.

But the team missed something important: regularization isn't one technique with universal settings. It's a collection of methods that work differently depending on your data and model architecture. The techniques aren't complex. But apply the wrong technique or tune it poorly, and you add computational overhead while the overfitting continues.

What is regularization in machine learning?

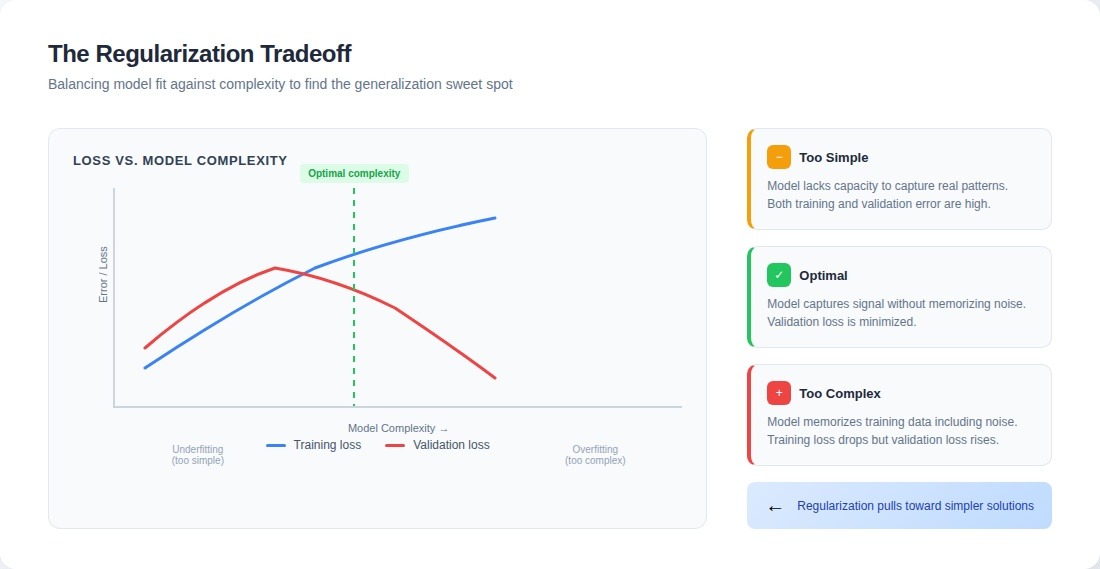

Regularization is a set of techniques that penalize model complexity during training. It adds a cost not for wrong answers, but for elaborate ones. L1 and L2 weight penalties, dropout, early stopping, and data augmentation all work differently but share a common premise: a model that needs complicated machinery to fit the training data probably learned noise along with the signal.

Rather than ask only "how wrong are my predictions?", regularization forces the model also to consider "how elaborate is my solution?" It's built-in skepticism about complexity.

The most common techniques work through different mechanisms, but more on that later. These techniques work remarkably well when the training data accurately reflect the actual problem space. They force models to learn general patterns rather than specific examples. But they operate under an assumption often violated in production: high-quality training data.

Why models overfit

A model overfits when it learns specific examples so well that it fails to generalize. Rather than learn "this combination of features indicates fraud," it learns "this exact transaction is fraud." The difference matters enormously in production.

Overfitting arises from a fundamental asymmetry: modern models have millions or billions of parameters, whereas training data is a finite sample of possible inputs. A 10-million-parameter network trained on 50,000 examples can memorize each idiosyncrasy, outlier, and error included. We saw a sentiment model learn to associate "customer service" with negativity because three angry reviewers repeatedly used that phrase. Regularization isn't optional at scale.

In production systems, overfitting traces to three sources: insufficient training data relative to model complexity, poor data quality where noise approaches or exceeds signal strength, and distribution mismatch between training and production that only surfaces after deployment.

Mathematically: training accuracy climbs while validation plateaus. Operationally, it's subtler. Models handle 90% of production cases correctly, then fail unpredictably on the remaining 10%. These failures seem random until you realize similar examples never appeared during training.

How overfitting breaks production systems

When a model overfits, it doesn't just perform poorly on test data. It breaks in ways that cascade through business operations.

A customer support routing model achieved 94% validation accuracy in predicting ticket categories. Two weeks into production, average resolution time increased by 40%. The model memorized specific phrases from training tickets rather than underlying patterns. When users wrote "can't log in" instead of "unable to access account," the model routed incorrectly. Same problem, different words, complete routing failure.

A contract analysis system identified liability clauses with 96% precision—but only when clauses appeared in the third or fourth paragraph. That's where they appeared in training documents. When the same clause was moved to paragraph two, accuracy dropped to 67%. The model learned what liability clauses looked like in one document set, not what makes a clause indicate liability.

L1, L2, Dropout, and Early Stopping: How Each Technique Constrains Learning

Regularization isn't a single technique. It's a toolkit of constraints that work through different mechanisms. How each operates matters more than the mathematical definitions.

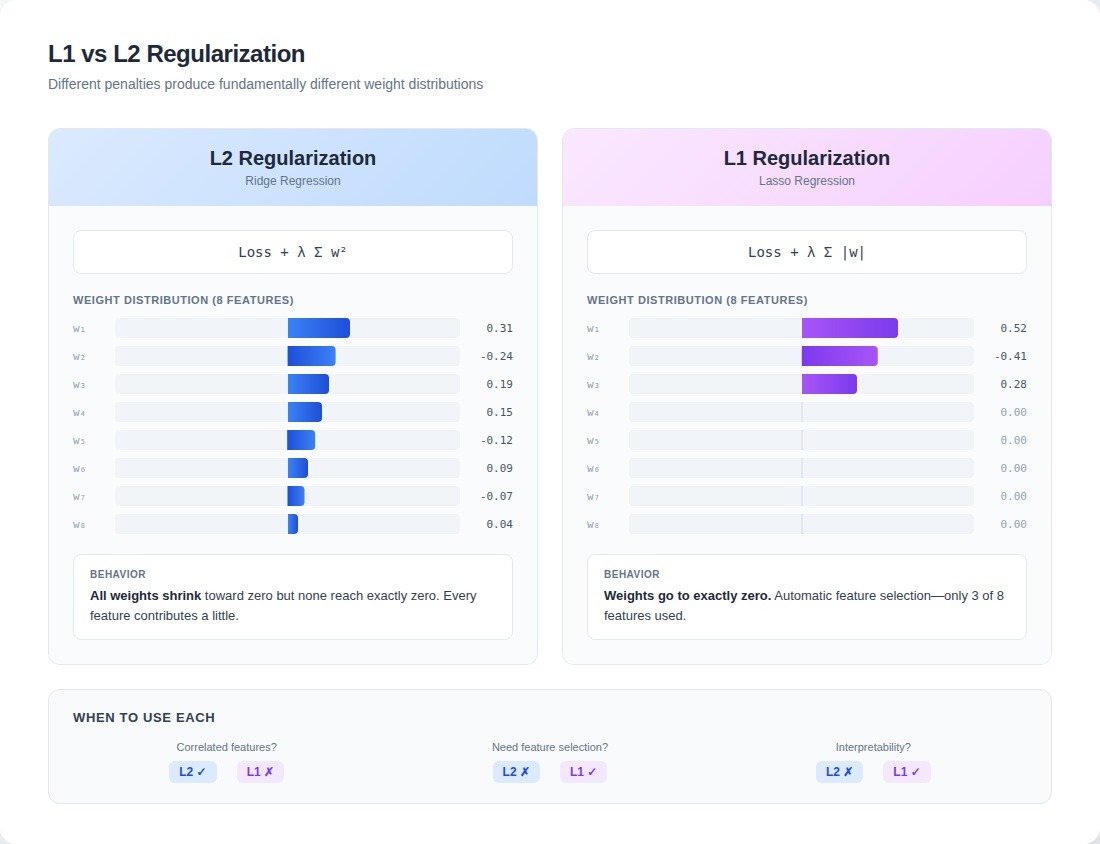

L1 and L2 regularization: weight constraints

The industry treats L1 and L2 as interchangeable hyperparameter choices. They're not.

L2 says: "Everything might matter a little." L1 says: "Find what actually matters and ignore the rest." That's not a tuning decision. It's a belief about your data.

- Production example for L2: A credit scoring model with 12 correlated income indicators (salary, bonuses, investment returns). L2 distributed weight across all 12; the model became robust to partial data.

- Production example for L1: A fraud team switched L2 to L1: 200 features shrunk to 23 active ones; accuracy stayed same; inference speed improved dramatically.

Both techniques only work when the relationship between penalty and generalization holds. If the training data has systematic gaps, regularization optimizes around them. It can't create absent information.

Elastic net: when you're unsure

Elastic Net combines L1 and L2 penalties, controlled by a mixing parameter α. Set α to 0.5, and you get both sparsity and stability — L1's feature selection with L2's handling of correlated predictors.

Why it's the safe default: high-dimensional dataset with unknown correlation structure? Start here. A fraud detection team inherited 200+ undocumented features. Elastic Net selected 31 while distributing weight across correlated transaction signals. Accuracy matched their best L1 attempt; robustness matched L2.

The tradeoff: two hyperparameters to tune (α and λ) instead of one. Cross-validation handles this, but computation cost increases.

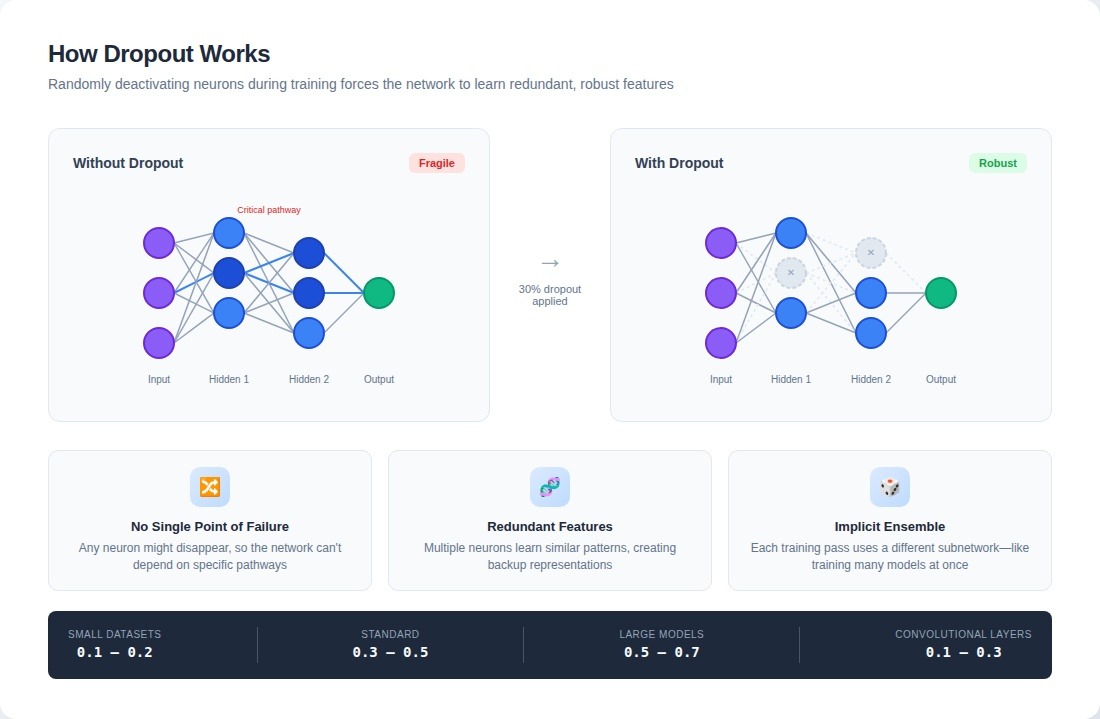

Dropout: robust features through random deactivation

Dropout breaks your network on purpose. Each training pass, random neurons disappear; 50% dropout means half the network goes dark. The logic sounds backwards until you see what it prevents: neurons that become load-bearing walls, so critical that the whole structure collapses without them.

The insight: dropout prevents any single neuron from becoming critical. A neuron might disappear at any moment, so the network can't build dependencies on specific feature detectors. It must learn representations that are both redundant and robust.

import torch.nn as nn

model = nn.Sequential(

nn.Linear(512, 256),

nn.ReLU(),

nn.Dropout(0.3), # 30% of neurons deactivated each pass

nn.Linear(256, 128),

nn.ReLU(),

nn.Dropout(0.3),

nn.Linear(128, num_classes)

)A computer vision model with aggressive L2 still showed a 15-point train-validation gap. Adding 0.3 dropout to dense layers closed that gap to 4 points. The model learned features that worked even with parts of the network absent.

Configuration matters more than most papers acknowledge. A team with 10,000 training examples used 0.5 dropout — a common default that was far too aggressive. The network couldn't learn stable features. Reducing it to 0.2 solved the problem.

Dropout also adds computational cost during training: more epochs to converge, effectively training an ensemble of subnetworks. At inference time, you need to scale activations correctly because all neurons are now active. Most frameworks handle this automatically, but we've seen production bugs where incorrect dropout scaling at inference created subtle accuracy degradation.

Early stopping and data augmentation

Early stopping is simple: stop training when validation performance degrades. No hyperparameters, no penalties. Just monitor the validation loss and stop when it increases for several consecutive epochs.

best_val_loss = float('inf')

patience, patience_counter = 5, 0

for epoch in range(max_epochs):

train_loss = train_one_epoch(model, train_loader)

val_loss = evaluate(model, val_loader)

if val_loss < best_val_loss:

best_val_loss = val_loss

patience_counter = 0

torch.save(model.state_dict(), 'best_model.pt')

else:

patience_counter += 1

if patience_counter >= patience:

print(f"Early stopping at epoch {epoch}")

breakOne team spent weeks tuning L2 and dropout for 82% accuracy. Early stopping alone hit 81%. The complex strategy bought one percentage point at significant engineering cost.

Data augmentation expands training data through transformations: random crops and flips for images, synonym replacement for text. A document classifier overfitted to fonts and margins; augmentation that varied formatting improved accuracy by 11 points.

But transformations must preserve labels. Random horizontal flips work for cat photos. They don't work for chest X-rays, where orientation is clinically significant.

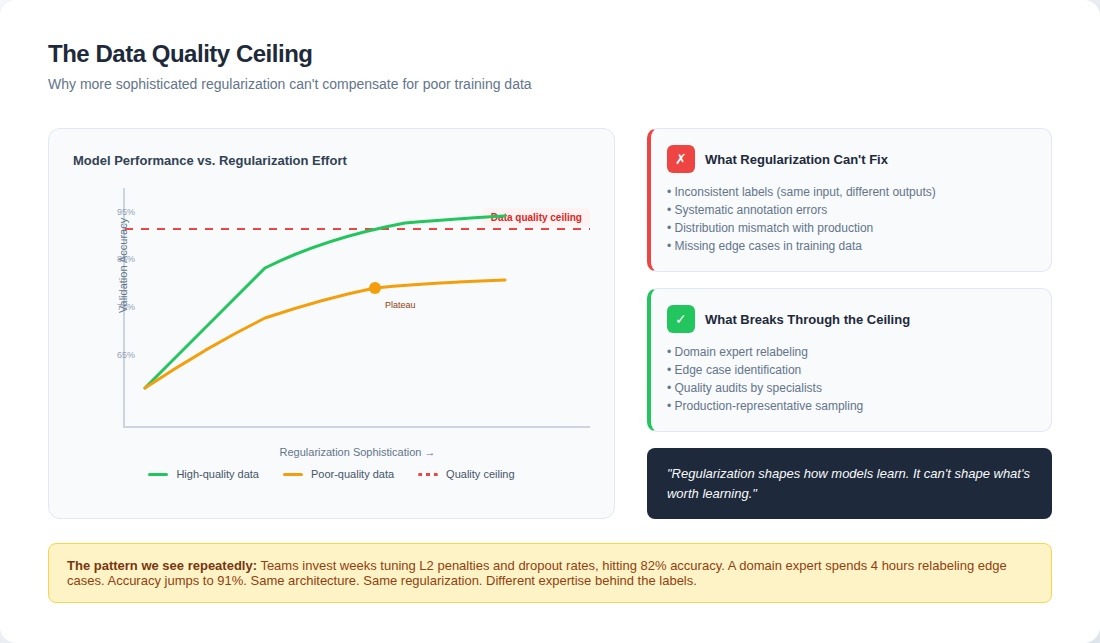

The data quality ceiling

This is the fundamental limitation teams discover too late: regularization shapes how models learn; it can't shape what's worth learning.

If labels are inconsistent, regularization helps the model ignore some of that inconsistency. It still learns some of it. If training examples don't cover the production distribution, regularization won't create coverage. It will just make the model more conservative within its limited observed distribution.

We tested this directly last quarter. A team brought us a highly regularized model: dropout at every layer, carefully tuned L2 penalties, and proper early stopping. It still failed because training data had systematic labeling errors in a specific edge case category. The model learned those errors as ground truth, just with more conservative confidence levels.

When expertise found what algorithms missed

A finance team shared a sentiment model that achieved 89% accuracy on their test set. In production, it flagged routine earnings reports as "highly negative" and missed actual risk signals.

We brought in a senior financial analyst with fifteen years of experience in public equities. She spent half that time parsing 10-Ks for a hedge fund. In four hours, she identified what the model had learned: the original annotators flagged any document that mentioned "risk" more than 5 times as negative sentiment.

The problem: regulatory filings require companies to enumerate risks even when business is excellent. A boilerplate 10-K might mention "risk" forty times with zero material concern.

She relabeled 2,000 edge cases based on actual risk indicators: earnings guidance revisions, unusual liquidity language, specific liability disclosures versus boilerplate. After retraining on her annotations, the model outperformed the original by 23 points on production data.

Same architecture. Same regularization. Different expertise behind the labels.

Why bigger models expose worse data

Teams discover overfitting, invest heavily in better regularization, then wonder why performance plateaus remain.

The missing insight: regularization sophistication and data quality requirements scale together, not independently. The more sophisticated your regularization becomes, the more it exposes the quality ceiling of your training examples.

We saw one dataset perform well from 1.3B to 13B parameters—then collapse at 175B. Approximately 12% of examples contained subtle label inconsistencies: functionally identical inputs with different annotations.

- At 1.3B, the model lacked the capacity to distinguish these cases

- At 13B, it learned an average behavior that generalized acceptably

- At 175B, it memorized the inconsistencies and tried to learn patterns from noise

When you apply dropout or weight decay to a larger model, you force it to extract more robust features from the existing signal. If that signal is noisy, the model learns to be robustly inconsistent.

Label noise that regularization masks

A content moderation system had a 15% disagreement rate. Aggressive dropout and L2 forced robust patterns — the validation metrics looked good. But the model had 92% confidence on controversial posts, split evenly between "allow" and "remove" based on trivial phrasing.

It learned to be confidently wrong: a smooth interpolation between contradictory labels. Worse than overfitting, because it appeared to be a successful generalization.

Distribution mismatch

A document classification model worked beautifully on a curated test set but degraded rapidly in production. Training data came from one large client: clean formatting, consistent structure. Production meant documents from hundreds of smaller businesses with OCR errors and casual language.

Accuracy dropped from 91% to 67% on differently formatted documents, even when the classification task was simpler. Regularization operates in the space defined by training data. It can't extrapolate beyond it.

The frontier isn't moved by better regularization alone or better data alone. Budget for both. Underfund either side, and you'll hit a ceiling you can't break through.

Textbooks teach regularization as a fix. Production teaches it's a constraint — and constraints can't create what was never there. Regularization teaches models to doubt themselves. But doubt without knowledge is just noise with constraints.

Contribute to AGI development at DataAnnotation

Regularization methods constrain how models learn. But what they learn depends entirely on the expertise behind data labeling, edge case identification, and quality evaluation.

If your background includes technical expertise, domain knowledge, or the critical thinking needed to evaluate complex trade-offs, AI training at DataAnnotation positions you at the frontier of machine learning. Over 100,000 remote workers have contributed to this infrastructure.

- Visit the DataAnnotation application page and click "Apply"

- Fill out the brief form with your background and availability

- Complete the Starter Assessment, which tests your critical thinking skills

- Check your inbox for the approval decision (typically within a few days)

- Log in to your dashboard, choose your first project, and start earning

No signup fees. DataAnnotation stays selective to maintain quality standards. You can only take the Starter Assessment once, so read the instructions carefully and review before submitting. Apply to DataAnnotation.

.jpeg)