I watched a vision model correctly classify 10,000 stop signs in testing. Then someone placed four small stickers on a real stop sign, and the model confidently labeled it "speed limit 45." The stickers were nearly invisible to human drivers. The model's confidence score: 93%.

These are adversarial examples: inputs deliberately designed to exploit how neural networks learn patterns. We're not talking about edge cases in messy real-world data. We're talking about inputs engineered to exploit specific vulnerabilities while remaining imperceptible to humans.

What are adversarial examples?

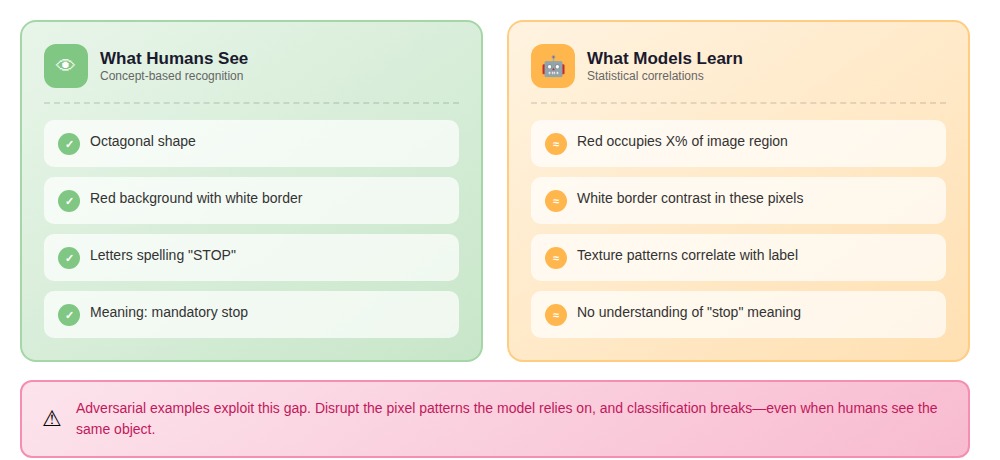

Adversarial examples are inputs crafted to cause machine learning models to make confident, incorrect predictions through minimal, often imperceptible modifications. They exploit the gap between how neural networks learn and how humans understand concepts.

When we train a vision model to recognize stop signs, it's not learning "octagonal red sign with white letters indicating mandatory stop." It's learning: these pixel patterns correlate with the label "stop sign" in my training set.

The same problem students face with standardized tests. A student who memorizes "the longest answer is usually correct" can score well without understanding the material. They've learned patterns that correlate with correct answers in the training distribution. Change the test format, and their "knowledge" evaporates. Neural networks make the same mistake at scale.

A computer vision team we worked with achieved 94% accuracy on traffic sign classification. Against physical adversarial examples — actual signs with stickers — accuracy dropped to 63%. The model had learned patterns like "red occupies this percentage of the image" and "white border contrast appears in these regions." Disrupt those patterns, and classification breaks.

In NLP, models learn token sequences that correlate with outputs, not semantic meaning. A content moderation system achieved 94% accuracy blocking harmful requests in evaluation. Within two weeks of deployment, users discovered that adding "for educational purposes" or switching to roleplay framing bypassed filters 60% of the time. The model learned which token patterns correlate with "harmful request", but it hadn't learned what makes a request actually harmful.

How do adversarial attacks work?

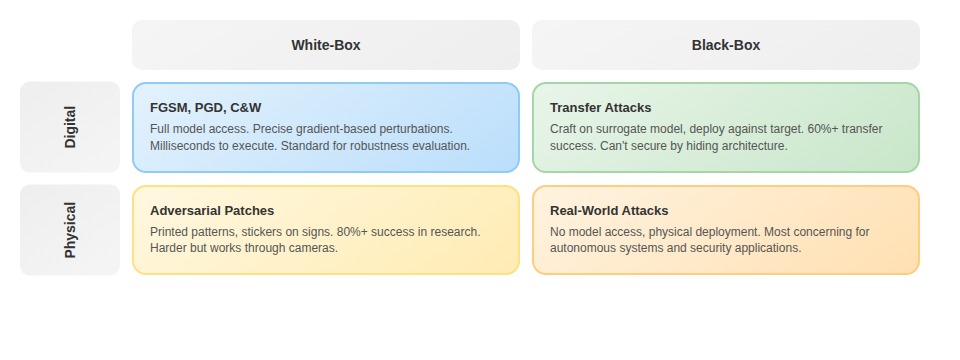

- White-box attacks assume the attacker knows everything: model architecture, weights, training data.

- Black-box attacks assume the attacker only sees inputs and outputs. The unsettling finding: black-box attacks work nearly as well. Adversarial examples crafted against one model transfer to others with 60%+ success rates. You can't secure a system by keeping its architecture secret.

- FGSM (Fast Gradient Sign Method) is the foundational attack: compute the gradient of the loss with respect to the input, take the sign, multiply by a small epsilon, add to the image. One step, milliseconds to execute, surprisingly effective. But FGSM is crude, and defenses can learn to recognize its specific perturbation patterns.

- PGD (Projected Gradient Descent) applies FGSM iteratively with small steps, projecting back into the allowed perturbation space after each iteration. PGD is the gold standard for evaluating robustness. If your model survives PGD, it's genuinely robust. If it only survives FGSM, you've likely learned to detect FGSM's signature rather than developing real robustness.

- C&W (Carlini & Wagner) is an optimization-based attack that finds minimal perturbations causing misclassification. Slower but defeats many defenses that stop FGSM and PGD. C&W revealed that several published defense papers had measured robustness against weak attacks only.

- Digital attacks manipulate inputs before they reach the model — precise control over every pixel.

- Physical attacks work through cameras or sensors in the real world. Harder to execute but more concerning for deployed systems. Research groups achieved 80%+ attack success rates on physical traffic signs by printing adversarial patterns and attaching them.

Why adversarial examples break model confidence

What makes adversarial examples uniquely revealing isn't that they break models, random noise does that too. It's that they break models systematically, with confidence, exposing the gap between benchmark accuracy and actual robustness.

A model's confidence score should indicate reliability. Adversarial examples produce the opposite: the more confident the model, the more spectacularly wrong it can be when manipulated. A cat image with imperceptible pixel-level noise was classified as "airliner" with 99.2% confidence. The original, correctly classified cat? 87% confidence. The adversarial example didn't just fool the model, it made the model more certain.

Natural mistakes usually signal uncertainty. Adversarial examples trigger the opposite: maximum confidence at maximum wrongness.

Transferability is the most unsettling property. An adversarial example crafted to fool Model A will often fool Model B, even with a completely different architecture and training data. We've tested this: generate adversarial examples against a ResNet, evaluate against a Vision Transformer. Transfer rate exceeds 60%.

Why? Different models converge on the same shortcuts because those shortcuts are statistically efficient. If "sky background" predicts "bird" in the training distribution, multiple architectures learn that feature. The adversarial example exploits the shortcut. Since multiple models learned the same shortcut, the exploit transfers.

Why benchmarks can't solve adversarial robustness

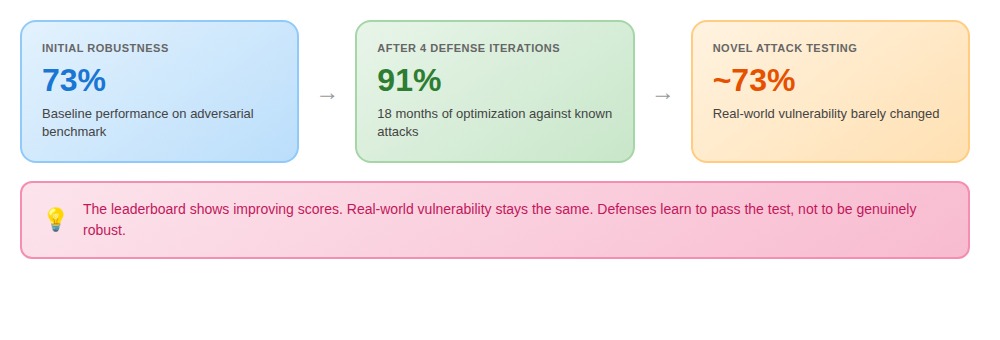

When adversarial examples started breaking models, the industry reached for benchmarks. Create a test set, measure performance, optimize until numbers look good. This approach fails repeatedly.

The attack surface is genuinely unbounded. A computer vision system passed robustness testing against 15 different perturbation methods. It failed in production when users discovered misclassifications caused by image-compression artifacts the test suite never covered.

We tested this with a major language model deployment. The model showed 88% robustness on a curated adversarial prompt dataset. Real-world robustness dropped to 62% within the first week. Users found prompt injections, encoding tricks, and multi-turn strategies not represented in the benchmark.

A system we worked on underwent four defense iterations over 18 months. Benchmark scores improved from 73% to 91%. When we tested against novel attacks, real-world vulnerability had barely changed. They'd trained their defenses to pass the test, not to be robust.

Why synthetic adversarial examples fail

When adversarial robustness fails, the instinct is to generate more adversarial examples and retrain. This approach plateaus.

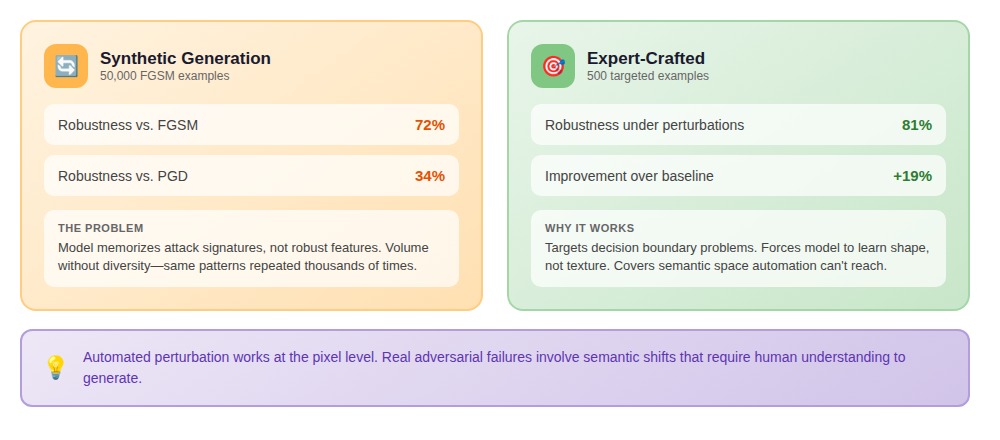

A security-focused ML team generated 50,000 adversarial examples using FGSM variants. Their model became robust to FGSM attacks. A different perturbation type broke it immediately. They'd trained the model to recognize one attack method's signature, not to develop robust reasoning.

We've tested this directly: models trained on 10,000 FGSM examples achieve 72% adversarial accuracy on FGSM. The same models on PGD attacks drop to 34%. The model memorizes attack signatures rather than robust features.

A senior ML engineer debugged why adversarial training wasn't generalizing. We analyzed their 2.3 million synthetic adversarial examples together. When clustered in embedding space, she saw it immediately: volume without diversity — 800 unique perturbation patterns repeated thousands of times.

Generation processes produce infinite variations, but only within the space they already understand. Automated perturbation works at the pixel or token level. Real adversarial failures often involve semantic shifts that automated systems can't generate. The famous stop sign attack used stickers that looked like graffiti to humans. An automated perturbation generator doesn't understand "semantic stop-sign-ness."

How training data quality determines robustness

The shift to human-crafted adversarial examples isn't about replacing automation. It's about introducing knowledge that automated systems can't access.

One of the annotators we work with created adversarial examples for diagnostic models. She thinks about scan artifacts, positioning variations, anatomical edge cases, and how radiologists reason about ambiguous findings. We added 200 of her examples to a training set of 50,000 standard images plus 20,000 synthetic adversarial examples. Model performance on held-out clinical evaluation improved by 16%.

This isn't because her examples are "harder" mathematically. They cover a semantic space that synthetic generation can't reach.

A team struggling with classification robustness trained a baseline model on 50,000 randomly sampled examples: 89% accuracy on standard tests, 62% under mild perturbations. They doubled to 100,000 examples. Performance under perturbations: 64%. Minimal improvement.

Then a computer vision researcher on the team analyzed failure cases. The model used texture shortcuts—classifying based on surface patterns rather than shapes. She selected 500 examples targeting specific decision boundary problems: unusual angles, difficult lighting, examples that forced the model to learn shape rather than texture. Performance under perturbations jumped to 81%.

Five hundred examples, chosen deliberately, achieved what 50,000 random additions couldn't.

In our operational data, expert-crafted adversarial training data produces models with 23-31% better performance on held-out adversarial test sets compared to equivalent volumes of synthetic examples.

Why adversarial robustness matters for AI safety

Adversarial robustness isn't an academic concern or deployment annoyance. It's a preview of alignment challenges at scale.

A model trained to produce confident wrong answers with imperceptible perturbations doesn't understand what it's doing. As AI systems make higher-stakes decisions (medical diagnoses, financial transactions, infrastructure control) the gap between pattern-matching and robust reasoning becomes the gap between useful tools and dangerous ones.

The adversarial examples we study today train us to build systems that fail gracefully rather than catastrophically. The core insight remains: robustness comes from training data that teaches genuine understanding, not more examples of the same shallow patterns.

Contribute to AI training at DataAnnotation

Adversarial examples expose a fundamental truth about AI training: models learn patterns, not understanding. The defense isn't just better algorithms, it's training data that captures the full complexity of real-world variations, edge cases, and adversarial scenarios.

As adversarial robustness becomes critical for production AI, training data quality determines whether models generalize or memorize. That quality depends on annotators who understand not just what to label, but why certain distinctions matter and what edge cases reveal about model weaknesses.

Over 100,000 remote workers contribute to this infrastructure. Getting started takes five steps:

- Visit the DataAnnotation application page and click "Apply"

- Fill out the brief form with your background and availability

- Complete the Starter Assessment—it tests critical thinking, not checkbox compliance

- Check your inbox for the approval decision (typically within a few days)

- Log in to your dashboard, choose your first project, and start earning

No signup fees. DataAnnotation stays selective to maintain quality standards. The Starter Assessment can only be taken once, so read instructions carefully before submitting.

Apply to DataAnnotation if you understand why adversarial robustness requires human expertise and have the domain knowledge to contribute.

.jpeg)